This Holy Saturday, between Good Friday and Easter, I was reflecting on the idea of Jesus as the slain Passover lamb. The association is certainly Biblical, not only in the obvious context of Jesus’ death taking place on Passover, but also in the testimony of the Apostle Paul in 1:Cor. 5:7. Paul doesn’t go into detail what he means about Jesus being the Passover lamb, but if we look carefully I think there are some helpful hints to be gleaned … hints that suggest Jesus’ shed blood means a great deal besides forgiveness of sins.

This Holy Saturday, between Good Friday and Easter, I was reflecting on the idea of Jesus as the slain Passover lamb. The association is certainly Biblical, not only in the obvious context of Jesus’ death taking place on Passover, but also in the testimony of the Apostle Paul in 1:Cor. 5:7. Paul doesn’t go into detail what he means about Jesus being the Passover lamb, but if we look carefully I think there are some helpful hints to be gleaned … hints that suggest Jesus’ shed blood means a great deal besides forgiveness of sins.

The Passover sacrifice is, of course, introduced in Exodus 12. In this account, God instructs Moses to tell the people of Israel to slaughter a lamb and do two specific things with it: mark their doorposts with its blood, and eat the flesh for dinner. In stark contrast to the usual Christian narrative of sacrifices being for sin, I find it notable that the concept of sin does not appear in the entire tale from Exodus 11-13. Both actions–the blood and the flesh–have a very specific purpose, and neither is related to sin at all.

First, the Israelites were to mark their door frames with the lamb’s blood “as a sign.” Those whose houses were so marked would not suffer the death of their firstborn, as happened to the rest of the households of Egypt. It’s important to recognize that God didn’t “need” the label; some (though not all) previous plagues specifically spared the Israelites in Exodus 8:22 (flies), Exodus 9:24 (livestock died), Exodus 9:26 (hail), and Exodus 10:23 (darkness). So the sign of the blood clearly was intended for the Israelites themselves, not so much for God and the angel of death. Nevertheless, the sign was clearly one of identification. The blood on the door marked a household not only as of the people of God, but people who had deliberately obeyed God’s command. It was not the shedding of that blood–the sacrifice itself–that spared the Israelites from the death plague, but rather the application of that blood according to God’s instructions. Might this be consistent with a God who prefers obedience to sacrifice (1 Sam. 15:22, Hosea 6:6)?

Second, the Israelites were to eat the roast flesh of the lamb. No symbolism is given for this in the Exodus text, and in fact the only instructions are that it should be roasted not boiled, that it be eaten in haste and with unleavened bread, and that any leftovers be burned. Without trying to extrapolate too much, I honestly wonder if this may not have been a highly pragmatic command for the simple reason that the people were about to travel on foot out into the desert, and they simply needed a good protein-and-carbohydrate meal to fortify them for the journey. God’s commands can get downright practical at times.

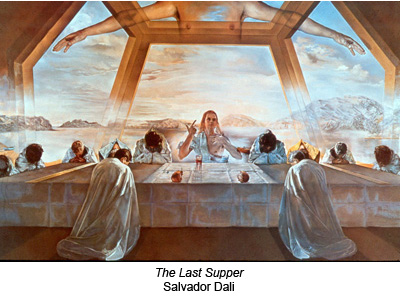

We Christians pay too little attention to the Passover links to Jesus, I think. Passover is the time when God called his people out of a foreign place, saving them from slavery, and in a very real way making them into “his people” in a way they had not previously been. On the eve of their salvation, on the threshold of a new life as a newly-created nation, God’s people were labeled by blood and strengthened by flesh of a sacrificed lamb. Paul says something quite similar in Ephesians 2:13-14, where even we Gentiles have been “brought near by the blood of Christ,” and separate peoples have been made into one “in his flesh.” Jesus told his disciples to eat of his flesh and drink of his blood at the Passover meal. Just as God initiated a feast of remembrance on the eve of delivering the people of Israel, Jesus instituted a new meal of remembrance as he set in motion the new kingdom of his Body. The body of Christ as well as the blood; the bread as well as the cup, is given to humans to unite and seal us as the people of God. In his broken body and shed blood, we are marked as different, set apart from the death that rages around us, and ushered into a new kingdom.

There is much more in the Bible about the blood of Christ, and I don’t suggest for a moment that the Passover narrative is the whole story. Still, it is one we should remember. This “day of remembrance,” this “festival to the LORD,” is to remind us of our deliverance, our calling, our unification as the people of God. Let us not forget.

I deeply appreciate your highlighting of Jesus’ death as inextricably linked to the Passover narrative – I too wrote something very similar last year in my blog. I think it’s a crucial and overlooked aspect.

I especially appreciate your pointing out of how the sign was not needed since the preceding plagues did not require any. I hadn’t fully considered that.

The one place I struggle with this paradigm though is in the addition to the equation of ‘forgiveness of sins’ – that is, where does the forgiveness of sins via the shedding of blood play into the ‘Paschal lamb’s sacrifice as the symbol of Adonai’s mercy, grace, and favour?’ It’s something I’d like to further explore, and I’m curious as to what your initial thoughts might be, if you understand what I’m trying to get at.

But perhaps I’m over-complicating the ‘mysteries of God’ and mixing too many metaphors, as it were.

In any case, Happy Easter Weekend and thanks again for another great read.

Thank you, Eric, for the comments. In partial answer to your question: there is nothing about the Paschal lamb that has anything at all to do with the forgiveness of sins. Passover isn’t about sin.

Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, is about sin: see Leviticus 16. Interestingly, there are sacrificial “sin offerings” as part of Yom Kippur, that “make atonement,” not only for the priest and the people themselves, but also for the Tabernacle and the Holy Place and the altar (see Lev. 16:15-20). These “atonements” have a sense of cleansing about them; the actual removal of the people’s sin takes place through the release of the live “scapegoat” of Lev. 16:21-22. While I don’t presume to understand all the symbolism here, it seems clear that the sacrifices of Yom Kippur are no simple quid pro quo for forgiveness of sins. There is such a quid pro quo implied in other places where specific sin offerings are made–see Lev. 4:20 for an example–but this is by no means universal.

It’s important to remember that Jesus forgave sins on his own God-granted authority and entirely apart from his blood. Luke 5:20-24 is an excellent example, in which Jesus explicitly states that he “has authority” to forgive sins, and offers as evidence his healing of the paralytic. Interestingly, Jesus’ forgiveness as related in the gospels hardly ever even comes at the request of the forgiven. Our paradigms need some adjusting, it seems to me.

Of course, the classic passage in defense of blood-for-forgiveness is Hebrews 9:22, which people usually only quote in part: “without the shedding of blood there is no forgiveness of sins.” The fact that they don’t even quote the whole verse does irreparable damage to the actual message. Go back and read the whole verse: “Indeed, under the law almost everything is purified with blood, and without the shedding of blood there is no forgiveness of sins.” We are not under that law, and in fact those who are Gentiles never were under it. The message of the New Covenant includes the fact that for those who were under the Mosaic covenant, Jesus has fulfilled it, but the Christian penchant for placing all of us under the Mosaic law before Christ can free us from it is starkly unbiblical.

Hope this helps. I’d love to push the dialog further. In the meantime, may the blessing of the risen Christ be on you!

Yes, I’ve often wondered what Jesus’ teachings at the time of Yom Kippur would’ve looked like. 🙂

You bring up some good points – much food for thought. By way of clarification, what I understand you saying is that Jesus’ bloodshed exacted Israel’s forgiveness as prescribed by the code of Torah – but we who are not under the Law do not necessarily need the shedding of blood for forgiveness. Is that a correct summation?

It’s an interesting point – one I’ll have to give further thought to, but it certainly has initially opened up further veins of exploration and perhaps parallels the Exodus and the Crucifixion much more closely – at least at this cursory glance.

I suppose my original question stemmed from a musing on ‘sin’ and its role in atonement theology, and perhaps that it is.. over-emphasised. If the Passover is a significant lens through which to see the crucifixion, then it is much more about the freedom (undeservedly) given, the unification of a people (in this case not only Jew, but also Gentile alike), and the favour bestowed thereupon. Thus, to put it pithily (too pithy perhaps?) what’s sin got to do with it? Jesus was forgiving people’s sins, by the authority of Adonai, prior to his death, as you mentioned, so his death might have a different overall focus.

I suppose I shouldn’t overlook your final point of the blog – that the Passover narrative is not necessarily the whole story – but these are simply some thoughts I’ve been playing with. I’ve not read much NT Wright, but from what little I have I understand that he goes into Jesus’ role as embodying Israel and thereby treats his death in context – much like from what I understand of Andrew Perriman.

Full disclosure: I’ve yet to look further into Pauline epistles on the matter. I’m merely recounting my initial inklings as you’ve prompted them.

Thanks for your time, by the way. I hope I haven’t burned away too much of it.

Eric, regarding “Jesus’ bloodshed exacted Israel’s forgiveness as prescribed by the code of Torah,” I would say a qualified “yes.” I think, though I have not studied the subject exhaustively, that even Torah teaches sacrifice as much as thanksgiving for sin already forgiven, as it does sacrifice as a forgiveness transaction. This is so much clearer in prophets such as Isaiah and Micah who make clear YHWH is far more interested in obedient hearts than material sacrifices. So I would revise your summary–I believe in harmony with the Apostles–to say “to whatever extent forgiveness was predicated on sacrifice, Jesus’ death satisfied those requirements once for all.” Jesus’ death fulfilled, not only the Torahic sacrificial requirements, but also those of any other religion in the world that requires sacrifice. In Jesus sacrifice-as-worship is no longer relevant. But yes, to the second part of your summary, “we who are not under the Law do not necessarily need the shedding of blood for forgiveness.” Yes, that’s exactly what I’m saying.

I do think your question “what’s sin got to do with it?” has genuine merit. As I pointed out in my own Enough With Salvation Already! post, to whatever extent sin is burdening you, Jesus took care of it. But no one needs to manufacture a feeling of burden in order to appropriate the life of Jesus.

And no, you’re not “burning too much” of my time. I love this stuff, and any time one more person asks the probing question, my work is being fulfilled. Thank you so much for inquiring!

Those who would wish to redefine the gospel must run head into the Lord’s own words on the night of his betrayal. By setting up this memorial meal and investing it completely with meaning that relates to the atoning of sin, and by declaring that they observe this until he comes, he was defining the Christian message in a way that is hard to set aside or redefine.

“Redefine the gospel?” I’d challenge you that these words are at best hyperbole and at worst just plain wrong. Let’s look at the words of our Lord on the night he was betrayed: Matt. 26:26-29, Mark 14:22-25, and Luke 22:14-21. Of those three accounts, only Matthew even mentions forgiveness of sins (and note Matthew was most committed to the fulfillment of *Jewish* scripture in Jesus); Mark and Luke say nothing of the sort. All three refer to “the blood of the covenant” which is a different thing entirely from atonement.

Re: the Lord’s Supper I encourage you to look at my post In Remembrance of Me for another take on what Jesus was doing.

I look at everything through the len’s of Jesus and he said in Matthew

Mat_9:13 But go ye and learn what that means, I will have mercy, and not sacrifice.

Later he declares people are condemning others because they do not understand

Mat_12:7 But if ye had known what this means, I will have mercy, and not sacrifice, ye would not have condemned the guiltless.

2,000 years and we still don’t understand that El Shaddai never wanted sacrifices. The anonymous author of Hebrews who was a classic flip-flopper says he is quoting Jesus (he doesn’t say from which source)

Heb 10:5 For this reason, when Christ came into the world, he said, “‘You did not want sacrifices …

Heb 10:6 You did not approve of burnt offerings and sacrifices for sin.’

Heb 10:8 In this passage Christ first said, “You did not want sacrifices, offerings, burnt offerings, and sacrifices for sin. You did not approve of them.”

Wow that means all the stuff about sacrifices written by the Apostles, church fathers, and all the Old Testament sacrifices were man made. All the stuff about blood cleaning sin was false. In the New Covenant sins are forgiven without blood. Jesus never called himself a lamb. He said he was a shepherd. Other called him a lamb going back to John the Baptist who never followed him and died in doubt. Look at the father of the two prodigal sons. He didn’t even require repentance. The son was home and it was all about joy.